When my father, the Rev. Clarence McMahan, turned eighteen on April 10, 1945, he was immediately drafted into the United States Navy. Following boot camp, he was assigned to the massive naval base at Norfolk, Virginia where an important skill got him a job well above his Seaman First Class pay grade. He could type.

This unique ability and his sharp mind made him so valuable that he was soon the senior clerk in the Navy’s enormous dry goods facility, the equivalent of many modern grocery stores combined. The war ended before he was shipped overseas, so he spent his military time typing orders for groceries for base personnel and ships at port.

When I was twelve years old, I owned a 410 shotgun, given to me by my dad’s best friend, Bill Bolin. Bill and I loved to hunt — mostly squirrels, rabbits and dove. I once asked my father why he didn’t hunt with us. He said he believed a person should never take something he couldn’t return. Taking a life, even the life of an animal, is taking something you can’t return.

For all my father’s life he was a gentle, kind, and enormously generous person. He was six feet, five inches tall and had a commanding presence when he entered a room. But his kindness and his inclusiveness pierced the hearts of everyone with whom he came in contact, and that’s what they remembered about him. When he died four years ago, I was surprised that he wanted military honors at his funeral. To my knowledge, other than his boot camp training, he had never fired a weapon of any kind.

On a cool day in March 2015, the Gaston Country Military Honor Guard turned out en masse for his funeral. Standing at parade rest, dozens of men, veterans of many eras and wars, formed a semi-circle around the tent where his body lay. Through tears of grief and gratitude I spoke one on one to each of these men and thanked them for honoring my father, as they have honored so many before and since. Following the graveside prayers, rifles fired into the air. The American flag was removed from the casket and folded. That flag and those shell casings sit prominently on a shelf in my den.

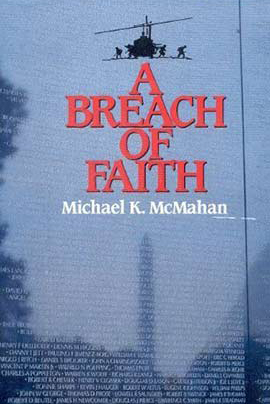

When I enlisted in the Army in 1966, I promptly told my drill sergeant that I could type. Eighteen months later I was slogging through rice paddies in Vietnam carrying an AR-15, as much ammo as I could cram into my backpack, a chest full of grenades, a .45 caliber pistol, and a combat knife. I was not a store clerk. I did my best as a soldier, and I’m proud of my service, but so was my father, a man who never wanted to take another person’s life, or any life, for that matter.

Most veterans are like him. They served their country doing whatever job their skills and circumstances dictated. But the service of all of our veterans was and is essential for keeping our country free. Let’s salute them all today, and tell them we’re grateful for their sacrifice and proud of them and their service.